St. Kilda is a residential suburb on Port Phillip Bay, 6 km. south-east of Melbourne.

During 1841-42 a cargo yacht “Lady of St. Kilda” was anchored in the bay, having been placed there for sale or barter. A colonial historian, Henry Gyles Turner, recorded that J.B. Were had an interest in the yacht and selected the raised sea side knoll at St. Kilda as the place for a picnic. The yacht’s captain was apparently present. From that event it appears that the place was named after the yacht. (The yacht’s name was presumably taken form the Hebridean island of St. Kilda.)

In December, 1842, allotments from a government survey were sold in the vicinity of Fitzroy Street and Lower Esplanade. Further lots were sold between 1846-51, by when St. Kilda was becoming an address of the well-to-do. The route to St. Kilda from Melbourne was a sandy track, commencing at a bridge (1846) over the Yarra River. The track was unsafe for travellers, and Strutt’s “Bushrangers” painting was reputedly inspired by an event on the St. Kilda road. An early hotel at St. Kilda, the Royal, was functioning by 1849.

Churches and schools began in St. Kilda in 1849, establishing a rich pattern of religious and educational institutions. The Anglicans held their first service in December, 1849, opened Christ Church and a school in 1851 and the present building in Acland Street in 1854; a second parish, All Saints, opened its church in Chapel Street in 1861. The Catholic church opened a church and school in 1853 in St. Kilda East. The Wesleyans held their first service in 1853 and built a church in Fitzroy Street (1857) which is on the Victorian Heritage Register. Presbyterians acquired a church in 1855 and the Free Presbyterians in 1864. Both churches built permanent buildings in Chapel Street.

In 1857 a railway line was built from Melbourne to St. Kilda, and a connection loop between St. Kilda and Windsor railway stations brought increased patronage to the privately run sea baths, the jetty promenade and the St. Kilda Cup was run at a racecourse near the Village Belle hotel. Cricket and bowling clubs were formed in 1855 and 1865. By the mid 1860s St. Kilda had about fifteen hotels including the George, formerly the Seaview (1857). St. Kilda by then was a borough (1863), having been proclaimed a municipality separate from Melbourne city on 24 April, 1855.

In 1870 Moritz Michaelis, a Jewish importer and merchant, built “Linden”, his residence at 26 Acland Street. The next year he and several other Jewish residents met to form the St. Kilda Hebrew Congregation. Michaelis laid the foundation stone for a synagogue in Charnwood Street. When Michaelis died at Linden in 1902, St. Kilda had a well-established Jewish community. The community has a land mark synagogue at the corner of St. Kilda and Toorak Roads and several religious and educational institutions extending eastwards to Elwood and Caulfield.

St. Kilda’s population more than doubled between 1870 and 1890 to about 19,000 persons. The opening of tram services to St. Kilda in 1888 and 1891 brought more pleasure seekers, somewhat lowering the tone and impelling the well-to-do towards South Yarra and Toorak. The 1890s depression caused several of the large mansions to be subdivided for apartment or boarding-house accommodation. “Oberwyl” was a spectacular example of a mansion built in 1856, whose owner failed in the 1870s, and the building became a school.

Wimpole’s Visitors’ Guide to Melbourne, Fredk. Wimpole, The George Hotel, 1881.

The pier and breakwater were constructed in sections between the late 1850s and 1884, adding to St. Kilda’s attraction. The Esplanade was landscaped and lit. In 1903 The Australian Handbook described St. Kilda as –

St. Kilda’s reputation for outdoors pleasure was enhanced by the formation of a council foreshore committee in 1906. It had the services of Carlo Catani an experienced engineer, who designed much of the foreshore reclamation and the Catani Gardens at the end of Fitzroy Street. The foreshore was hired out to open-air showmen, a forerunner to Luna Park (1912). St. Kilda’s mass-entertainment function was further broadened by the Palais de Danse (1913), which became a cinema two years later when a second dance venue was built.

St. Kilda changed from being a patrician village to a carnival – spectacular St. Kilda – according to its historian, J.B. Cooper (1930). However, its was not altogether a classless carnival, St. Kilda pier, the Esplanade and the St. Kilda Road boulevard provided an ideal entry point for vice regal and other visitors, such as Lord Brassey (1895), the Duke and Duchess of York (1901), Lord Jellicoe (1919), the Prince of Wales (1920) and the United States Pacific Squadron (1925). Cooper devoted two chapters to them. These events, however, became interludes during a trend to raffishness. Some of metropolitan Melbourne’s first flats were built amidst St. Kilda’s boarding houses and night-time entertainments were joined by brothels and street prostitution. The parks were a cheap substitute for rented rooms, and motor cars provided mobility. Melbourne City Council’s efforts to clean up Little Lonsdale Street in the 1930s forced women to work south of the Yarra. In 1932 St. Kilda’s V.C. hero, Albert Jacka, ex-Mayor, died, at a time when the depression was biting into the livelihoods of residents and local entertainers.

The depression, however, heightened the yearning for entertainment, and the Palais de Danse enjoyed strong attendances, as did the Palais Theatre (1927). In 1939 the St. Moritz ice-skating rink was opened in a former theatre which, between 1933 and 1935, had been the film studio for Frank Thring’s Efftee productions.

During the 1930s flat construction outnumbered house construction in St. Kilda by about ten to one. The growth in population density was high, and local shopping centres were enlarged.

The outbreak of war brought enlistments by local men and women, and the Pacific war brought American troops to Australian shores. St. Kilda’s entertainment precinct was a magnet for Australian and American services personnel. The artist Albert Tucker painted some memorable “Images of Modern Evil”, inspired by his observations of Australian good-time girls and soldiers on leave. On the other hand an illustrated pamphlet with verse composed round the popular tune “Thanks for the Memory” seemed to equally well capture the wartime relationships for many others.

During 1941-3 the Prest social survey conducted by the University of Melbourne confirmed that St. Kilda’s grand days had come upon mixed fortunes. Among the well off there were genteel poor, and lodgers and poor families were crowded into decayed residences.

The American invasion retreated as the Allied forces advanced on Japan. Another invasion in the postwar years was increasing cosmopolitanism, as immigrants journeyed to the beach for outings. Foreign menus were added to St. Kilda’s eateries. Candidates for Council election, however, became involved in clean-up campaigns, alarmed by deviant behaviour, crime, prostitution and drunkenness, but the council was unwilling to acknowledge that standards had slipped.

More flats were built during the 1960s, mostly privately financed, and some on under-sized sites. Entertainment such as Whiskey-a-Go-Go and Les Girls became metropolitan venues, and the Council was content to focus on these aspects rather than welfare needs or a municipal library. In the late 1960s, however, contesting views on sexual behaviour were played out as Bertram Wainer campaigned on abortion and Germaine Greer, who grew up in Elwood, published The Female Eunuch. The Council was forced to confront unconventional behaviour in its area in the 1970s as evidence increased about massage parlours, drug trafficking and street kids.

Palais Theatre, circa 1997.

Despite those things the Palais hosted the annual film festival, artists and galleries increased in the 1980s and the Astor theatre changed to less commercial art films after having been a Greek-film cinema. The council was contested by reform-minded councillors, and a library was opened in 1973.

The physical make-up of St. Kilda was change by increasing traffic from Brighton Road through the St. Kilda junction. In 1968 road widening works were begun and the road south to Carlisle Street widened by 1975, involving demolition of the Junction Hotel and 150 other buildings. In 1969 the St. Kilda marina was opened, following on from the Royal St. Kilda Yacht club, becoming the Royal Melbourne Yacht Squadron and taking over the St. Kilda baths which had been built in 1928.

The St. Kilda Football Club moved its home ground to Moorabbin in 1964, after having been at the Junction Oval since before its joining the League in 1897. The emotional loss was compensated for by the Cub’s first premiership in 1966.

During the 1980s and 1990s St. Kilda became better regarded for its polite cosmopolitanism. Kerbside cafes near Acland Street’s superb cake shops drew tourists, and Acland Street became a pedestrian mall. An art and craft market was opened on The Esplanade in 1969. St. Kilda’s natural attractions became evident to new residents in search of apartments and restored cottages. Between 1987 and 1996 the median house price in St. Kilda increased form 165% to 182% of the metropolitan median.

During the course of St. Kilda’s social change its schools and churches have maintained a strong presence. In 1990 the municipality had five government school campuses and fourteen non-government campuses. St. Michael’s Grammar School (1895, co-educational), had 1,300 pupils from kindergarten to year 12 in 1992.

St. Kilda has parks and gardens on the foreshore, in Albert Park and of Blessington Street either side of Acland Street. There are shops in Fitzroy Street and in St. Kilda Road south of the junction.

On 22 June, 1994, St. Kilda city was united with South Melbourne and Port Melbourne cities to from Port Phillip city.

The St. Kilda municipality had census populations of 6,408 (1861), 20,542 (1901), 38,579 (1921), 58,318 (1947), 61,203 (1971) and 45,481 (1991).

Luna Park from the Dinghy Jetty, St. Kilda. Postcard by Rose Stereograph Company.

Cake shop windows, Acland Street.

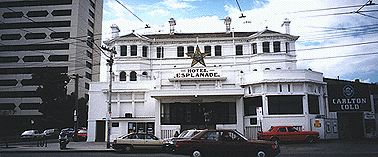

St Kilda scenes, circa 1997.

Further Reading:

- Cooper, J.B., “The History of St. Kilda From Its First Settlement to a City and After, 1840 to 1930”, 2 vols., Printers Pty. Ltd., 1931.

- Longmire, Anne, “St. Kilda: the show goes on: the history of St. Kilda, volume 3, 1930 to July 1983”, Hudson Publishing, 1989.

Interesting, good old st. Kilda???????? honestly pete – this is a fab website, well done pal.xx