Healesville is a township 52 km. east-north-east of Melbourne, just south of the Watts River which is a tributary of the Yarra River. Upstream from where Healesville is situated gold was foundat New Chum Creek in about 1859. By 1860 New Chum was a village. However,it was the creation of tracks to the more distant Gippsland and Yarra Valley goldfields in the 1860s that resulted in a settlement forming at Healesville and its survey as a town in 1864. It was named after Richard Heales, Premier of Victoria, 1860-61.

The first land sale at Healesville was in 1865,and in the following year there were thirty business premises, includingsix hotels and a primary school. Healesville was also selected as a sitefor “neglected black and half-caste children and an asylum for infirm blacks.” Thus the Coranderrk reserve on Badger Creek, south of Healesville,was created in 1865.

Healesville was situated on the most convenient coach route to the goldfieldsin the Woods Point area, and it was the place where fresh horses were takenfor the ascent to Fernshaw and Blacks Spur. In 1881 The Australian Handbookdescribed Healesville as –

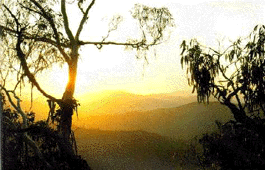

As the Gippsland goldfields declined some miners took up farm occupations in Healesville. Timber cutters found employment, and hop gardens were established.In 1881 the railway had been opened between Hawthorn and Lilydale, 12 km.south-west of Healesville. Expectation of the railway’s extension to Healesville stimulated business and population growth. In 1889 the railway link was opened, two years after the Healesville shire had been created on 30 September,1887. The scenery of Fernshaw was more readily reached from the Healesville train terminus and tourism entered Healesville’s local economy. Gracedale House of 60 rooms was built in 1889.

Farming developed in the newly cleared Don and New Chum Creek Valleys.Upstream on the Watts River the Maroondah Weir was built in 1891, the watershed requiring the removal of the Fernshaw township and curtailment of timber cutting. In 1893 the library and Mechanics’ Institute was opened. Despitethe limit put on timber cutting, Healesville’s economy grew – day outingsand travel to cool mountain retreats brought hundreds of people. The Australian Handbook’s description of Healesville in 1904 was –

Orchards and vegetable growing increased their acreages, along with a successful increased tobacco plantation. Elaborate country-retreat residences were built alongside hotels and guest houses, and a Tourist and Progress Association was created before 1914. In the 1920s the Association published “Healesville, The World-famed Tourist Resort”, listing over 40 beauty spots and 20 hotels and guest houses. The construction of the Maroondah Dam in 1927, replacing the weir, brought several hundred workmen to Healesville.Their departure, and the onset of the 1930s depression exposed Healesville’s restricted range of industries. Timber and tourism were not stable enough for sustained growth. Notwithstanding the depression, the 1930s saw increased motor tourism, partly bypassing Healesville, and decreased railway patronage.Only 10% came by rail in Easter, 1934. Tourism was still active but a local newspaper commented that Healesville would be “heaps better off callingitself the good-time town instead of the world-famed-tourist-resort – that’sgot whiskers on it.”

In 1934 the Sir Colin Mackenzie Sanctuary for Australian Fauna and Flora was opened on land that was formerly part of the Coranderrk reserve. The Healesville Sanctuary became one of Victoria’s premier tourist attractions.

The outbreak of the second world war stimulated timber cutting, which initially concentrated on harvesting trees damaged in the extensive Black Friday bushfire of January, 1939. The early postwar years saw a resumption of traditional Healesville tourism, while petrol shortages lasted, but motortravel gradually made Healesville a wayside stop for many travelers. The Australian Blue Book described Healesville shire in 1949 as –

Forestry operations in he 1940s had increased Healesville’s population,and continued activity was required to sustain them. During the 1950s theshire unsuccessfully contested the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Worksview that the watersheds should be kept unlogged. Small industries makingfoundation garments, knitwear, electrical appliances and soft drinks contributedto a much needed diversification of employment activities. The Golf Houseguest house was taken over the for RACV Country Club in 1951. In January,1957, a new hospital was opened and in 1961 the central school (1952) wasreplaced by a high school. A new swimming pool was opened in 1964.

Healesville shire until the 1950s had undergone only minor boundary adjustments. However, the relatively close Yarra Glen had more in common with Healesville than with Eltham shire, and the Yarra Glen district wasadded to Healesville shire on 18 June, 1958. Northwards, Buxton went toAlexandra shire on 1 October, 1963. Healesville remained the larger commercialcentre in its shire, having 64 commercial establishment compared with 35in Yarra Glen in 1988.

The township has a comprehensive range of facilities. In addition tothe shopping centre there is a district hospital, Queens Park with a swimmingpool and sports facilities, a showgrounds and sporting complex, five churches,halls, Catholic school and State primary and high schools.

Healesville shire ceased on 15 December, 1994 when part was united withparts of Whittlesea city and Diamond Valley shire and most of Eltham shire to form Nillumbik shire. The other part was united with Alexandra and Yea shires and parts of Whittlesea city and Broadford, Euroa and Eltham shires to form Murrindindi shire on 18 November, 1994. At that time Healesville shire contained the localities of Badger Creek, Christmas Hills, Toolangiand Yarra Glen.

Healesville’s census populations have been 207 (1881),907 (1901), 2,035 (1933), 3,566 (1954) and 6,264 (1991).

Healesville shire’s census populations, after most of the significant boundary changes, were 5,941 (1961), 9,670 (1981) and 11,755 (1991). The urbanisation of Healesville shire was reflected in the median house price rising from 70% to 80% of the metropolitan average between 1981 and 1986.

Further Reading:

- Symonds, Sally, “Healesville, History in the Hills”, PioneerDesign Studio, 1982.