Broadmeadows is a residential and industrial suburb 16 km. north of Melbourne and until 1994 it was a municipality.

The lightly wooded landscape between the Merri and Moonee Ponds Creeks attracted pastoralists in the 1840s. In 1850 a Government survey laid out a township in an area along the Moonee Ponds Creek valley, now known as Westmeadows, but then named Broadmeadow. An Anglican church was built in 1850, and the church, police station and Broadmeadows hotel (now Westmeadows Tavern), in Ardlie Street were the first village centre. The old Council chamber and office are nearby.

East of the old village is today’s Broadmeadows, for which the early town centre was Campbellfield. In 1857 the Broadmeadows District Road Board was formed. Its area had Essendon on the south and it extended as far north as Mickleham, placing the village very much in the southern third of the Road District.

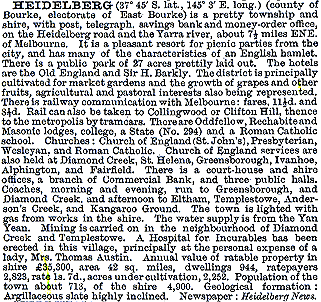

A primary school was established by the Anglican church in 1851, becoming a State school in 1870 (now Westmeadows). In 1872 the railway line was extended form Essendon to Seymour, creating a station about 2 km. east of the village. At the height of the landboom in 1889 another line was opened from Coburg, joining the Seymour line at Somerton. A station was provided at Campbellfield. These lines tended to draw subdivision and speculation eastwards, away from the Broadmeadows village. Hence the naming of the local municipal council as Broadmeadows shire on 27 January, 1871, did not reflect where the district’s future prosperity lay. The village was isolated westwards, separated from the railway areas by open grass lands. Broadmeadows consisted of farms, many of them dairying, and the few large holdings were subject to closer settlement subdivision during the early 1900s. The shire was enlarged on 1 October, 1915, when the shire of Merriang, to the north-west, was added. In 1903 The Australian Handbook described Broadmeadows as –

Two weeks and one day after the outbreak of the first world war the Australian Army established the Broadmeadows Military Camp in the open area between Broadmeadows and Campbellfield. Reticulated water was connected in five days, a project which the shire had been unable to persuade the Board of Works to undertake in seven years of negotiation. The camp and the surrounding areas were the venue of numerous bivouacs and military exercises.

Residential subdivisions had been released in the shire’s southern areas since the 1880s, and much of the land was not built on by the end of the first world war. More subdivision took place in the 1920s, and Broadmeadows had its (railway) Station Estate. Reticulated water and electricity were connected to the southern part of the shire in 1924 and 1925, and the railway was electrified in 1921. In 1928 new shire offices were opened near the railway station. These conveniences, plus the quicker travelling time to Melbourne, potentially made Broadmeadows more appealing for residential settlement. The line through Campbellfield, however, was closed between 1903 and 1928, when an infrequent service was resumed. During the 1930s financial depression the military camp accommodated unemployed men. The Broadmeadows landscape, however, remained one of small farms and derelict, undeveloped subdivisions, amounting to 17,000 allotments. In 1949 The Australian Blue Book described the Broadmeadows shire as –

In 1951 the Victorian Housing Commission announced its proposal to take over 2,270 ha. of land in Broadmeadows for a housing estate. The Commission’s housing construction proceeded apace, but the provision of shops and other facilities lagged. Glenroy became the main lcoal shopping area, four kilometres to the south. Schools were opened in time for the new population: Broadmeadows East and Broadmeadows South (later Glenroy North), in 1956, and Broadmeadows and Eastmeadows in 1961, the latter also attended by children from a migrant hostel in the military camp. The Commission built in the area between Broadmeadows and Glenroy in 1958, and the Jacana and Campmeadows primary schools were opened the following year. During the 1960s three secondary schools were opened – two technical and one high. Catholic schools comprise a primary, a co-educational secondary and a boys’ secondary.

Some way through Broadmeadows’ urbanisation it was decided to sever the rural parts north of Somerton Road and attach them to the adjoining shire. This occurred on 31 May, 1955, and next year on 30 May Broadmeadows was proclaimed a city. Six months later the Housing Commission began the transfer of a wedge of its land at Upfield and Campbellfield for the Ford motor car factory, which reactivated the railway which had been closed (again) the previous year. The Ford factory opened in 1959 and four other substantial factories opened the following year along the Hume Highway.

Schools were overcrowded, swimming pools unbuilt until 1962 and speech nights were held at Coburg or Essendon. A new civic hall and council offices were built in 1964. The adjoining local shopping centre, Meadow Fair, existed only on Housing Commission paper until the 1970s, and finally in 1974 it was completed. It is now the Broadmeadows Shopping Square, considerably enlarged to over 20,000 sq. metres of gross lettable area. The site for a hospital, however, still remained empty in the mid 1990s.

During the 1970s and 1980s Broadmeadows had a reputation for boisterous youth: the Broady Boys rode the trains and daubed graffiti proclaiming that they “rule, O.K.” By the 1990s this had lessened and there was a catch-up of some of the facilities long denied. Jacana gained a golf course, much of Westmeadows is a reserve, the town park and a TAFE are opposite the civic offices and there are two reserves beside the reduced military barracks. The technical school site is occupied by an Islamic College and there are four other secondary colleges. Space is reserved for further enlargement of the shopping centre, but public libraries are in other town areas under the Council’s jurisdiction (1996).

The Broadmeadows municipality contained Campbellfield, Collaroo, Dallas, Fawkner, Gladstone Park, Glenroy, Oak Park, Tullamarine, Upfield and Westmeadows. (Some of these contained smaller localities which are mentioned in their descriptions.) On 15 December, 1994, Broadmeadows city was united with most of Bulla shire and parts of Keilor and Whittlesea cities to form Hume city.

Broadmeadows’ census populations were 333 (1861), 192 (1911) and 522 (1947). The municipality’s census populations have been 2,100 (1911), 8,971 (1947), 23,065 91954), 66,306 (1961, after severance of the northern area), 101,100 (1971) and 102,996 (1991).

Further Reading:

- Lemon, Andrew, “Broadmeadows: A Forgotten History”, City of Broadmeadows and Hargren Publishing Company, 1982.